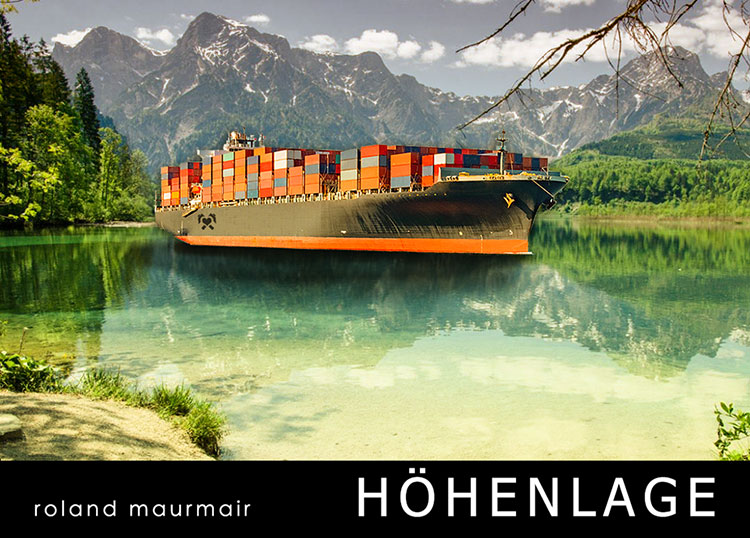

Höhenlage

Einzelausstellung | solo exhibition 2022

Galerie und Kunsthandel Verena Konzert

Erlerstrasse 15

6020 Innsbruck

Dauer | Duration: 11.03.– 15.04.2022

ÖFFNUNGSZEITEN

Mo – Fr: 09.00 – 12.00 und 15.00 – 18.00 Uhr

Höhenlage

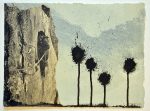

In der historischen Betrachtung erweist sich der alpine Raum auf vielfältige Weise nutzbar. Die Landwirtschaft, die die erste Form der wirtschaftlichen Nutzung der Alpen darstellte, ist heute noch genauso präsent wie vor Tausenden von Jahren. Weitere wichtige Wirtschaftsfaktoren waren lange Zeit der Bergbau und die Forstwirtschaft, die zwar heute weitgehend vom Tourismus abgelöst wurden, deren Auswirkungen auf die alpine Lebenswelt aber noch bis heute spürbar sind, denke man beispielsweise an das Lawinenunglück von Galtür im Jahre 1999. Für die von der im Tiroler Unterland angesiedelten Bergbauindustrie benötigten Holzmengen wurden seinerzeit weite Teile der Waldflächen im Tiroler Oberland gerodet. Der fehlende Schutzwald war die Ursache für dieses Unglück, das damit eine eindeutige und traurige Folgeerscheinung dieser bergbauwirtschaftlichen Nutzungsform darstellt. Mit der Industrialisierung und dem aufkommenden Alpinismus begann auch eine zunehmende touristische Nutzung unserer Berglandschaft. Damit einhergehend zeigte sich erstmalig eine „ästhetische Eroberung der Alpen“1, die heute nach dem Volkskundler Bernhard Tschofen in einer totalen Popularisierung des Alpinen gipfelt.

Die Folgen dieser verschiedenen Nutzungsarten werden beispielsweise in der Urbanisierung des ländlichen Raumes2 ersichtlich, wie sich auch eine zunehmende Veränderung der ursprünglich landwirtschaftlich genützten Kulturlandschaft zu einem Gelände für Abenteuersportarten jeglicher Art abzeichnet. Die ökologischen und kulturellen Folgen, – dass immer mehr Skipisten und Autobahnen unser Landschaftsbild prägen, sind mittlerweile zwar absehbar, eine weitere Entwicklung ist nicht gänzlich erfassbar.

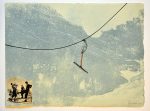

Wie sich zeigt, haben die Industrialisierungsprozesse von Landwirtschaft, Bergbau und Tourismus unsere Landschaft mitgeformt und auch den Blick auf unsere Heimat beeinflusst.3 Dienten Seilbahnen ursprünglich vorrangig zum Gütertransport, werden diese im Zuge des aufkommenden Tourismus vermehrt für den Transport von Personen zu den Aussichtsplateaus verwendet. Der Blick auf die Landschaft veränderte sich, gleichermaßen wie sich auch die Bestellung von Grund und Boden veränderte.

Die Fahrt wird zu einem Erlebnis und bietet dem Blick neue Optionen. Für Paul Virilio ist es ein „kinematischer Aufnahmeapparat“, der das Auge in Bewegung versetzt und ein „Mittel zur Vergrößerung der Reichweite des menschlichen Blickes“4 darstellt.

Wird vielleicht bald die Betrachtung einer klischeehaften Idylle unserer schönen erholsamen Almgegend abgelöst von einem Blick der sportbegeisterten Adrenalinjünger?

Wird eine satte Almwiese in Hinkunft in den Augen mancher Extremsportler als mögliche Downhill-Strecke wahrgenommen werden?

Die Gesellschaft ist im Hochgebirge angekommen.

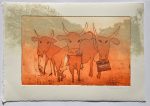

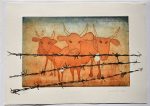

Mit der zunehmenden menschlichen „Nutzung des alpinen Raumes“, ist dieser auch mehr und mehr in den Fokus unserer Betrachtung gerückt. Lawinen- und Murenabgänge dienen der medialen Berichterstattung als Katastrophenmeldungen, „Kuhattacken“ erfordern ein Handeln auf politischer Ebene. Konflikte zwischen Jägern und Tourengeher bzw. Mountainbikern stehen an der Tagesordnung, Naturschützer kämpfen gegen Seilbahnbetreiber. Wie sich zeigt treffen im Gebirge nicht nur Mensch und Tier aufeinander, vielmehr ist dieser Raum zu einer Spielwiese verschiedene Interessensgruppen geworden.

Laut der Warnungen von wissenschaftlicher Seite, schmelzen uns die alpinen Gletscher vor der Nase weg; – bis dato sind die daraus resultierenden Auswirkungen für das Individuum kaum spürbar. Wie lange noch? Wird eine zunehmende Verstädterung der Alpen vonstatten gehen, wenn in den Tälern kein Platz mehr ist? In welcher Weise verändert die zunehmende Nutzung des Alpinen die identitätsstiftende Heimatassoziation der Alpen? Verwittert unsere Kultur gleichermaßen wie die Berge um uns erodieren?

Es wird deutlich dass Kultur und Landschaft sich gleichermassen in einem stetigen Wandel befinden. Wobei es doch auf jeden Schritt ankommt und diesen mit Bedacht zu setzen, wenn man in unwegsamen Gelände unterwegs ist.

1 TSCHOFEN, Bernhard: Berg Kultur Moderne. Volkskundliches aus den Alpen. Wien 1999, S.47

2 Vgl. : BÄTZING, Werner:

Die Alpen. Entstehung und Gefährdung einer europäischen Kulturlandschaft. München 1991

3 Anm.: Die touristische Nutzung ist mittlerweile in Form von Gruppen, wie zum Beispiel Alpenvereine und Naturfreunde traditionell verankert.

4 Vgl. VIRILIO, Paul: Rasender Stillstand. München/Wien 1992

Höhenlage (lit. High Altitudes)

Working in difficult terrains

From an historical point of view the Alpine region has proved usable in various ways. Agriculture, constituting the first form of economic usage of the Alps, today is just as present as it was thousands of years ago. Other important economic sectors for a long time have been mining and forestry, which today have mostly been replaced by tourism, whose effects on the Alpine habitat, though, are palpable to this day. Just think of the avalanche disaster in Galtür, in 1999. Wide stretches of the forests of the Tyrolean west were cut down for the mining industry further down the Inn valley and its demand for timber. The lack of protective forest was the cause of the disaster, which thus is a blatant and sad consequence of the economic exploitation. With industrialisation and rising Alpinism there also was an increasing tourist interest in the mountain landscape. Going hand in hand with the latter an “aesthetic conquest of the Alps”1, first became noticeable, which today, according to the ethnologist Bernhard Tschofen, culminates in a total popularisation of all things Alpine.

The effects of these various forms of usage become apparent, for instance, in the urbanisation of the rural areas2, just as an increasing transformation is looming on the horizon of the cultural landscape, originally used for agriculture, into an adventure sports playground of all kinds. The ecological and cultural consequences, namely that ski slopes and motorways dominate our landscapes, by now may be foreseeable, but a further development is not completely conceivable.

As we can see, the industrialisation processes of agriculture, mining and tourism have had their share in forming our landscape and also have influenced the way we see our homeland.3 While cableways originally mainly served the transportation of goods, in the course of rising tourism they have been primarily used for the transport of persons to observation decks. The view of the landscape has changed, just as the cultivation of land and soil has.

The journey becomes an adventure and offers the gaze new options. For Paul Virilio it is a “cinematic recording apparatus” which sets the eye in motion and constitutes a “means of extending the reach of the human gaze”4.

Will the observation of a cliché idyll of our beautiful, relaxing Alpine areas soon perhaps be replaced by the hungry gaze of sporting adrenaline junkies? Will a sumptuous Alp pasture in future be no more than a possible downhill track in the eyes of many an extreme athlete? Well, wider society has arrived in the high mountains.

With the increasing human “usage of the Alpine space” the latter also has moved more and more into the focus of our observation. Avalanches and landslides serve media coverage as news material. “Cattle attacks” call for action on a political level. Conflicts between hunters and ski tourers resp. mountain bikers are the order of the day. Environmentalists are locked in a stand-off with cableway operators. As we can see, it is not just humans and animals that meet in the mountains. The area much rather has become the playground of various stakeholders.

According to warnings from scientists, the Alpine glaciers are melting away before our very eyes. Up until now, the consequences are hardly noticeable for the individual. But for how much longer will they be? Will there be an increasing urbanisation of the Alps once there will be no more space in the valleys? In which way does the increasing exploitation of the Alpine regions change their identity-defining homeland association? Will our culture erode just as the mountains do around us? It is becoming ever clearer that culture and landscape are swept up in a constant process of change. Yet every step counts and so does taking it with caution when moving in dangerous terrains.

In the course of the Höhenlage (lit. High Altitudes) project artworks have come about that seize on the questions above and deal with them. An artistic confrontation with the high Alpine region has, to put it cautiously, the potential to open up new perspectives on the Alpine world.

1 Transl. from TSCHOFEN, Bernhard: Berg Kultur Moderne. Volkskundliches aus den Alpen. Vienna 1999, p. 47

2 Cf. BÄTZING, Werner: Die Alpen. Entstehung und Gefährdung einer europäischen Kulturlandschaft. Munich 1991

3 Note: The tourist use, thanks to the organisation in clubs such as Alpine Associations or environmental groups, by now has a rooting in tradition.

4 Cf. VIRILIO, Paul: Rasender Stillstand. Munich/Vienna 1992

internal link: • 0815